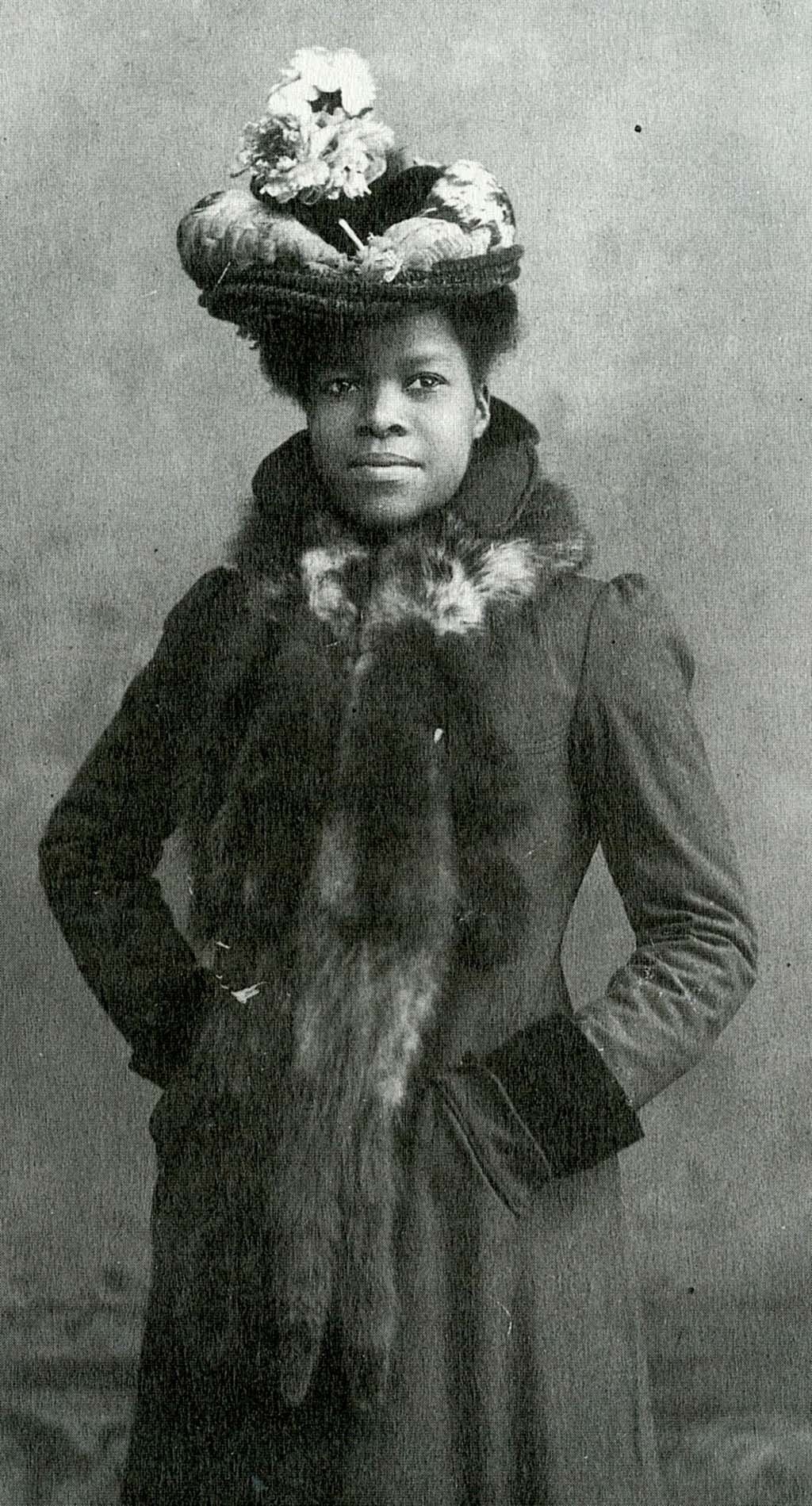

Nannie Helen Burroughs

Written by Stefanie Goldberg

b. May 2, 1879 | d. May 20, 1961

Fighting racism and sexism and with access to few resources, Nannie Helen Burroughs dedicated her life to providing quality education to young Black women, with a mission to enhance their personal, moral, and intellectual development.

“Until we realize our ideal, we are going to idealize our real.” - Nannie Helen Burroughs

Nannie Helen Burroughs was one of the best known and most well-respected figures among African Americans of the early twentieth century. A born educator, institution and organization-builder, and civil rights advocate for African Americans and women, she dedicated her life to pursuing education, excellence, and equality.

Born on May 2, 1879 to John and Jennie Burroughs in Orange, VA, Burroughs grew up in Washington D.C.; it was to the latter that Jennie brought Nannie and her sister, in search of a better job and the educational opportunities D.C. offered for Blacks. Burroughs was deeply influenced by her childhood, raised solely by her mother without the presence or assistance of her father (who died when Burroughs was very young); this experience gave her a profound respect and admiration for the strength of the poorer Black working class, especially women.

Drawn to learning and education, she graduated with honors from the prestigious M Street High School, hoping to join her distinguished teachers as a teaching assistant in the public schools for Black youth in Washington DC. Despite her credentials, her application was rejected likely as a result of color prejudice, as suggested by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham (202); put simply by historians, Jess McHugh writes, “the Black people doing the hiring believed her to be ‘too Black’” (McHugh). Burroughs saw this as an opportunity to use her disappointment to one day create an educational institution for Black young women founded in equality.

Burroughs worked her way into leadership in 1900, only 21 years of age, when she gave a speech on women's equality entitled “How the Sisters are Hindered from Helping” at the National Baptist Convention (Harley 66). This speech served as the impetus for the formation of an auxiliary of the National Baptist Convention, the Women's Convention, the largest Black women’s organization of which Nannie became president.

Burroughs’ vision of establishing a school for Black women and girls was adopted by both the National Baptist Convention and the Women’s Convention. She believed in the dignity and value of women’s work as well as the need to improve the employability of Black women, which her institution would espouse; as Higginbotham wrote, Burroughs wanted to redefine black women’s work identities as “skilled workers rather than incompetent menials” (Harley 3). In October of 1909, her dream became a reality when the National Training School for Women and Girls was opened in the Lincoln Heights section of Washington DC, the “culmination of many of Burroughs’ ideas about work, female respectability, and racial self-help” (Harley 65). While many similar institutions of this era were established through the funding of white philanthropists (the Tuskegee Institute and Hampton Institute, for example), the National Training School was unique in that it was initially funded solely by the African American community (Taylor).

Though the National Training School was non-denominational, Christian beliefs and practices were a core tenet of the institution. The school required its students and teachers to be deeply committed to a stringent religious environment. In addition to their industrial and vocational training, these women were being educated in religious service. Burroughs wanted her pupils to be prepared to do a “special type of ‘missionary work’: to teach the Bible in local churches, to be able to raise a family, or to go to foreign lands as Christian teachers” (Taylor 397). In her book What a Woman Ought to Be and to Do, Stephanie J. Shaw details how this emphasis on Christian morality and virtues was representative of most Black schooling between 1870-1930, a period that saw the growing influence of the Baptist church on Southern Blacks. However, it was this pillar or religion that Burroughs believed would support young Black women confront a long history of discrimination, “prepared to inhabit and make a living in an unjust world while being equipped with the leadership skills and sense of self-efficacy needed to change that world” (Bair 13).

Burroughs believed in putting forth your best effort no matter what the circumstances, in doing the ordinary in an extraordinary way; in her opinion, there was no job or task too menial to perform with great efficiency and professionalism. Aware that domestic service was a reality for most Black women, the school's curriculum emphasized vocational training and offered classes in domestic science, missionary work, social work, home nursing, clerical work, printing, dressmaking, beauty culture, shoe repair, and agriculture; she believed in the professionalization of domestic service, as this was Black women’s most prevalent occupation in the early 20th century. Devoted to women’s rights and the opportunity to receive a thorough education, classes were also provided in grammar, English literature, Latin, drama, public speaking, music, and physical education. Equally as important, the school had a “Department of Negro Studies” and students were required to take a course in Black history; Burroughs insisted that to understand the current plight, it was necessary to have knowledge about “past achievements and struggles about the race” (Harley 68). Burroughs created an institution that trained “women who would be self-sufficient and committed to the uplift of their race” (Taylor 391).

Burroughs’ legacy extends beyond the four walls of a building yet she has remained absent from many contemporary historical works about African American leaders and intellectuals. This could be attributed to her lack of a college degree, her strong identification with the black working class, her unwavering feminism, her racial pride. Scholars like Sharon Harley, Traki L. Taylor, Stephanie J. Shaw, and others are changing that narrative and writing Burroughs back into the historical landscape.

Burroughs wanted Black women to be ‘“public thinkers and not just public doers,”’ said Kelisha B. Graves, editor of Nannie Helen Burroughs: A Documentary Portrait of an Early Civil Rights Pioneer (McHugh). She established an educational institution that assisted young Black women in becoming politically and economically autonomous, and she believed that building a sense of self-efficacy and self-worth was “crucial to the development of their civic identities” (Bair 32). A prolific activist, Burroughs understood the intersectionality of racism, classism, and sexism, and used the power of thought and speech to challenge them. In a time of profound inequity, the stench of which still lingers today, Burroughs engaged young Black women in the call for racial uplift and supported them in the construction of their social, political, and economic identities.

Sources

Harley, Sharon. "Nannie Helen Burroughs: 'The Black Goddess of Liberty.'" The Journal of Negro History, vol. 81, no. 1, 1996, pp. 62-71.

Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. “Burroughs, Nannie Helen (1879-1961).” Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia, edited by Darlene Clark Hine et al, University of Indiana Press, 1993, pp. 201-205.

Taylor, Traki L. “'Womanhood Glorified': Nannie Helen Burroughs and the National Training School for Women and Girls, Inc., 1909-1961.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 87, no. 4, 2002, pp. 390-402. The University of Chicago Press Journals, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.2307/1562472.

Thomas, Veronica G., and Janine A. Jackson. “The Education of African American Girls and Women: Past to Present.” The Journal of Negro Education, vol, 76, no. 3, 2007, pp. 357-372.